Human beings have skated for millennia, but our history begins when people began skating for leisure in the 1700’s as documented by Robert Jones.1. Notably the books is a treatise on skating, not figure skating. In fact, the word “figure” in that sense only occurs once, in describing how “to cut the Figure of a Heart on one Leg.” So where did figure skating come from?

Figures, Figure Dancing and Figure Skating

Before people in the British Isles skated figures they danced figures. The earliest known use of figure dance is from 1672 in Westminster-drollery part 2. A figure is a named pattern of movement larger than a step but smaller than an entire dance; and a figure dance is constructed by combining figures into an entire dance. A Handbook of Irish Dances2 (1914) documents dozens of figures used in Irish Dancing with names such as “Advance and retire”, “Figure of eight”, “Hands round four,” “Ladies’ chain,” “Advance through centre,” “Loop and swing,” etc. These figures are designed to be danced by groups of dancers and the patterns created by the arrangement of dancers on the floor are often more important than the body positions or tricks performed by each individual dancer. Experienced dancers learn each figure by name and dances can proceed with a “caller” who calls each figure as it is to be performed.

This approach to group dancing, with figures and callers, is familiar to modern participants in dance from the British Isles: videos of Figure Dancing Championships are readily available on YouTube. And although this practice may be foreign to a modern figure skater, it is almost exactly how English Style Figure Skating worked, with the highest goal being Combined Figures. The Royal Skating Club in England continues this 200-year old tradition today.

Thus Figure Skating as embodied in the English Style is a direct descendant of Figure Dancing popular in England in the 1700’s and 1800’s. Human beings have been dancing since time immemorial, but only skating (for pleasure) for a few hundred years. It is not surprising that people will bring the aesthetics, practice and structure of their dances on to the ice when they begin skating. Of course the technique is different on ice vs. land. Our English forebears developed and systematized the technique of figures skating, resulting in the edges, 3-turns, brackets, rockers and counters — and much more — that we know and love today.

Patterns of Dance vs. Patterns on Ice

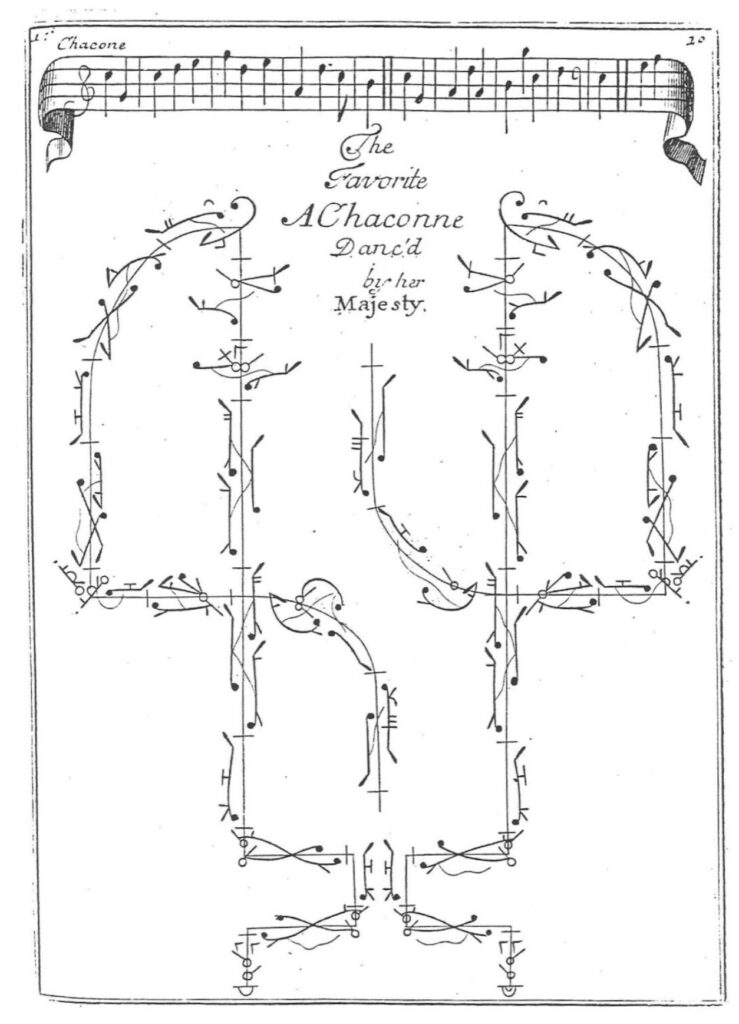

Baroque dances for the ballroom and stage were notated using Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, which was first commissioned by King Louis XIV. The pattern of the dance on the floor was drawn out, with steps drawn along the patterns, a concept familiar to figure skaters today:

The same was done for figure skating: in fact, 19th Century books the Art of Figure Skating are filled with drawings of this type. But the unique and special thing about ice — especially the grey or black ice prevalent at the time — is that a tracing is created on the ice as one or more skaters performs a figure. In fact the tracing on the ice becomes a record of what the human body was doing while skating the figure: every move or nuance is translated into an effect visible in the tracing!

Thus in the 19th Century the term figure came to have dual meaning in the context of skating: a named set sequence of moves, but also the pattern created by such moves. And terminology developed for many kinds of figures, related to both meanings. Figures to place are performed to retrace their pattern, with an orange cone marking the center in traditional English style skating; the term “figure” can refer to the tracing. Figures in the field (or free figures) do not have to retrace their pattern, and the term “figure” refers mostly to the older meaning of the word.

In 19th Century competitions, skaters would provide judges with drawings of the figures they planned to skate, whether to place or in the field. In time people developed additional categories of figures. What if you skate a figure but spend part of the time in the air, then continue the figure as if you’d never left the ground? Thus flying figures were born. It was in this context — as part of a figure — that Axel Paulsen introduced his Axel jump in 1882.

Most notable are special figures (called creative figures or figure artwork in the 21st century), in which the purpose is to leave an artistic tracing on the ice. All the top figure skaters between 1890 and 1910 would bring their special figures to competitions. Ulrich Salchow had a signature cross he would skate. The Russian skater Nikolai Panin, one of the world’s best in special figures, won the special figure segment of the 1908 Olympics — the one and only Olympics that included such an event. Here is his Panin Lake Special Figure:

And thus, the concept of figures — both a pattern of human movement and a pattern on the ice — became inextricably linked with the art of skating.

English, North American and Viennese Styles

Due to favorable climate conditions, large areas of snow-free ice and industrialization, skating figures first developed in England as a pastime for the elite, who would skate on frozen ponds in Hyde Park (London). Mid-19th Century English skaters developed the systematic technique we know today: not just 3-turns and inside/outside edges but also all other possible combinations, front and back, inside and outside. And thus we have 32 one foot turns including brackets, counters and rockers, along with dates that each of those types of turns was invented and named.

The ultimate goal of English Style skating is to skate combined figures3: figures with multiple people skating together, directed by a caller, which is similar to how English Country Dancing works. To make this look good, the training was focused on developing uniformity between skaters, similar to modern synchronized skating teams. And the uniform style chosen by the English consisted of a straight standing leg at all times (except when pushing), a reserved verticality, and a dislike of “awkward” or “kicking” motions required to skate many of the special figures. Thus English figures were skated on circles as large as possible, with participants needing a couple of pushes to gain speed before beginning the figure. The English Style was consistent with upper class and male gender expectations of Victorian England, and it took advantage of the large snow-free frozen areas available in England.

Skating developed in North America in the 19th Century based on the close cultural ties with the UK. But it differed because of the significant distance, different class culture and different skating conditions. In particular, New England’s harsher weather produced plenty of snow on top of frozen ponds, which must be cleared before skating, and large skatable areas were harder to come by. In contrast to the large combined figures of English Style Skating, North Americans came to excel at smaller complex figures with endless variety, for example the Maltese Cross. Hundreds of such figures are documented in books from the era, most notably George Meagher’s book on Figure and Fancy Skating from 1895. Contributing to basic technique, North Americans are credited with inventing the loop (and related ringlet); and also multiple variations of the grapevine.

The third nexus of the development of figure skating in the 19th Century was Continental Europe, most notably Vienna.4 The American ballet dancer Jackson Haines is credited with jump-starting interest in skating with a trip to Europe in 1867-68 and creating the International Style, however this is a gross simplification.

Ballet was first introduced to United States as early as 1735 and Jackson Haines did in fact study ballet in his native New York City. But ballet in the 19th Century was a strictly European affair, having grown out of the lavish European courts. Ballet in the United States was not a permanent institution like it is today and there was no American ballet companies or equivalent of the Paris Opera. Rather, it was a curiosity brought from Europe by a dancer here, a troupe there, typically presented as part of a variety show. Moreover, the defining feature of ballet as we know it today — the pointe shoe — was not fully developed until the 1890’s. Therefore Jackson Haines, coming from 1860’s United States with its variety shows, would be better described as a talented all-around performer, known for performing on stage, on roller skates, on ice skates — really any way possible.

Jackson Haines left the United States for Europe in 1865 at the height of the American Civil War — not a good time to be in the entertainment business. Apparently he was a sensation across Europe, and he landed in Vienna in 1868, just one year after the Wiener Eislaufverien (Vienna Ice Skating Club) was founded, and he helped the ice rink gain popularity. Just as the English style of skating developed from English styles of dancing, so did skating in Vienna develop from popular Viennese dancing at the time, in particular Viennese Round Dancing and the Waltz — skated to a band, jus as was done with floor dancing. And thus the Viennese gave us what ultimately became ice dancing.

By the 1890’s, Viennese figure skating was at least as elaborate as that practiced in England and North America, as documented in Spuren auf dem Eise (1892). The book describes a system of figure skating at least as elaborate as its contemporaries in North America and Europe: not only a variety of figures made up of edges turns and loops; but also special figures, jumps, spins and pirouettes (on a toe pick) are also described.

Thus by the 1890’s we see at least three highly developed, elaborate skating “scenes.” Although styles and preferences differed between Europe, the Continent and North America, it is clear from the books at the time that there was plenty of crossover, undoubtedly due to the rise of printed books and skaters traveling between locations. English skaters might have been known for their “stiff” style, but they were aware of what others were doing. North Americans might have been known for their special figures, but such figures were also popular in Europe.

Most importantly, figure skating in the 1890’s was universally considered to be an art. There were some skating competitions, for example the one Axel Paulsen attended in 1882. But many skaters, particularly in England, felt it was unseemly to compete in skating; anyway, the goal of English skating was not individual competition but to cooperate in a group activity. In any case, art competitions happen from time to time and holding one does not turn an art into a sport. Art is subjective and primarily concerned with aesthetics. Skaters certainly had their opinions and preferences: some complained the English skaters were too “stiff,” while others complained that the “acrobatics” needed to skate special figures were unseemly. Some skaters were primarily concerned with the art left on the ice, whereas others were more interested in how they looked while doing it. These are all subjective opinions with respect to a diverse set of practices at the time broadly known as “figure skating.”

The key word to describe the art figures skating in the 1890’s is diversity. This made it an exciting decade.

Figure and Fancy Skating

Continuous Skating

The Rise of ISU and Sportification

- Robert Jones, A Treatise on Skating, 1740 ↩︎

- J G O’Keefe, A Handbook of Irish Dances, 1914 ↩︎

- E.F. Benson, English Figure Skating: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Skating in the English Style, 1908 ↩︎

- Scandinavian skaters including Axel Paulsen and Ulrich Salchow played an important role too; however due to the climate, snow spots such as skiing developed more than ice skating

↩︎